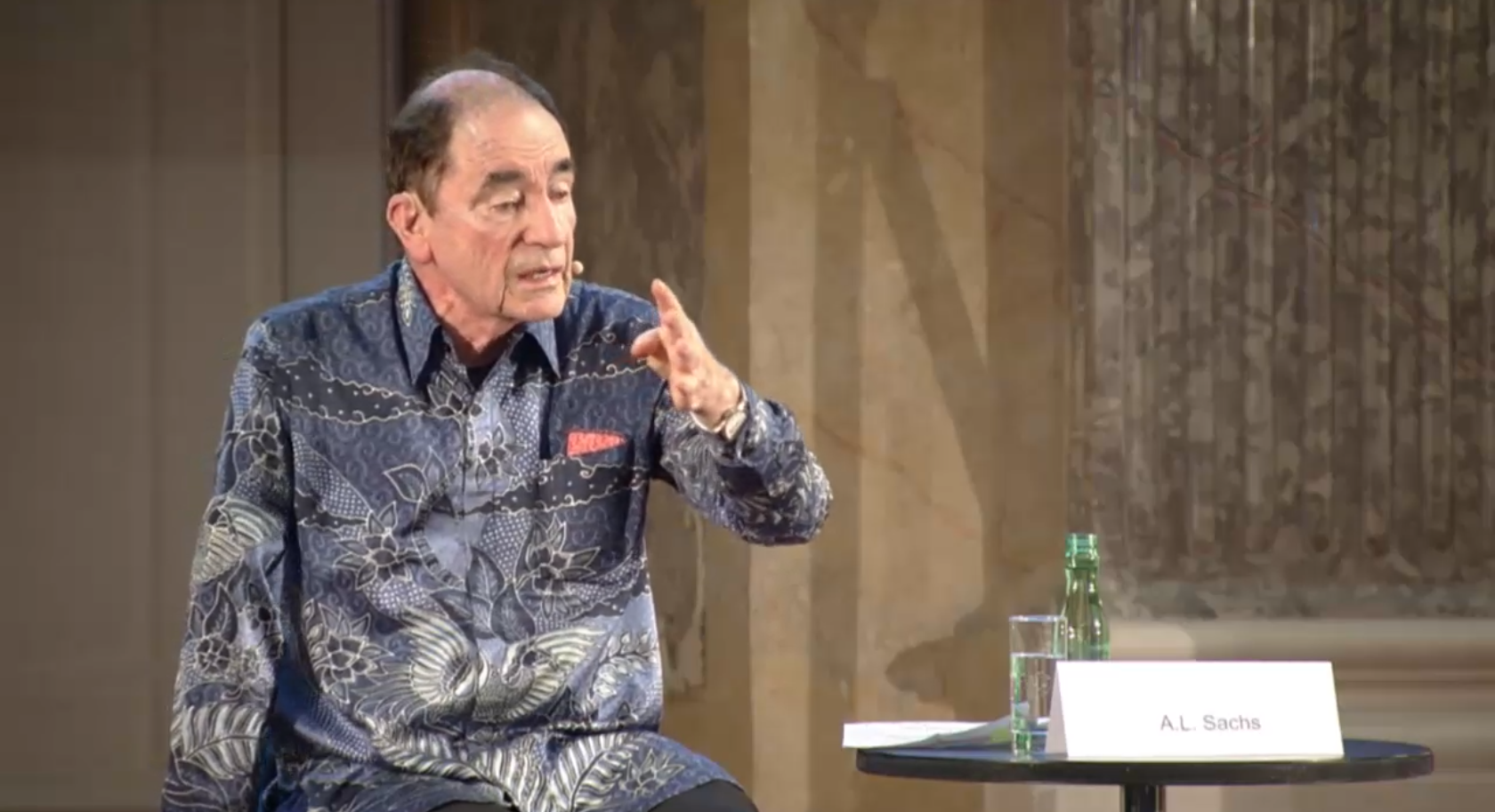

Sitting before an audience of scientists and policymakers from all over the world, Albert Louis Sachs, a former judge and a leading figure in South Africa's break from apartheid, told the story of a woman, Mrs. Grootboom, who just wanted a roof over her head.

Sitting before an audience of scientists and policymakers from all over the world, Albert Louis Sachs, a former judge and a leading figure in South Africa's break from apartheid, told the story of a woman, Mrs. Grootboom, who just wanted a roof over her head.

“She and thousands of others were living in a settlement – shacks, shacks, shacks after shacks – near Cape Town, were dreading the approaching winter rains,” said Sachs in his keynote lecture at the 26th TWAS General Meeting on Wednesday. “They’d be flooded out.”

This story was how Sachs began a moving speech at the Vienna, Austria meeting about the tensions within sustainable development. He discussed how science can be both a powerful force for lifting up people in poverty while also touching on how such efforts can be at odds with disadvantaged people like Mrs. Grootboom, whose right to a safe shelter from the rain ran into conflict with government housing development policy. The idea of sustainable development, he said, must never lose sight of human well-being as it becomes increasingly central to global policy.

Sachs was a lawyer in South Africa during the nation’s period of apartheid, mainly using his skills to defend those charged under repressive and racist laws, some facing death sentences. He went into exile in 1966 but continued his work. Then, in 1988 in Maputo, Mozambique, he lost his arm and sight in one eye to a car bomb placed by South African security agents. But in the years that followed he played a key part in establishing South African’s post-apartheid constitution. And after South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994, President Nelson Mandela appointed Sachs to the nation’s new Constitutional Court. He served as a judge on the court for 15 years, and was part of major decisions expanding human rights. He's the winner of the 2014 Tang Prize in Rule of Law.

See more news from the 26th TWAS General Meeting in Vienna, Austria

It was Mrs. Grootboom’s struggles that presented him with an unforgettable conundrum on that court. With rains coming, she and her neighbors felt they had no choice but to collapse their shanties and moved to a nearby hillside with proper drainage, he said. But they were evicted because others were already in the queue for low-cost housing. They ended up in a dusty sports field, Sach said, frustrated that they didn’t have a proper place to live. And in 2000, her case came before him and ten other justices in the South African Constitutional Court. He found himself asking, as South Africa pushed to develop sustainably and within its means, how could the court make the human right to have a home meaningful, when that right had been situated as a question for government policy, and not the law?

Sachs said that those seeking to develop the world sustainably must constantly keep such tensions that arise in mind.

“That whole theme of sustainable development is not allowing one part of the equation to dominate and crush other, or saying the answer is somewhere in the middle,” he said. “It’s finding a way of managing the tensions in a principled manner, that preserves our world and environment, but also looks to the sustainability not only of the Earth and its resources but of the human beings on the Earth. Human sustainability has got to be part of it.”

“And the poor can’t just be seen as anonymous masses to be moved this way and that for the sake of development, for the sake of future progress,” he added. “They have to be seen as human beings.”

With sustainable growth comes tension

The tension between the judiciary upholding fundamental rights and the government’s efforts to develop their countries is just one example of the kind of tensions that can arise as nations with tight resources try to provide essential human needs such as low-cost shelter. Sachs described several kinds of tensions that can emerge as science and policy combine on the path to sustainable development.

Globalization, which starts at one point and spreads all over the planet, can conflict with universalism in which the whole world cooperates equally. Within science there is tension between whether research should be done for business or for the public good. Also within science, there is a conflict between what Sachs called “warm and cold knowledge.”

Globalization, which starts at one point and spreads all over the planet, can conflict with universalism in which the whole world cooperates equally. Within science there is tension between whether research should be done for business or for the public good. Also within science, there is a conflict between what Sachs called “warm and cold knowledge.”

“For millions of people all over the world, warm knowledge is much more important than cold knowledge,” he said. “It’s the sustaining knowledge of the community. It comes from song and dreams and art and all sorts of cultural practices and customs. But it gives them stability and meaning. And the cold knowledge is the hard scientific knowledge and it’s often the gap between the two that leads to the hard scientific knowledge not being properly appropriated and aspects of the warm knowledge not being appreciated by countries that want to be scientific.”

Sachs cited South Africa’s having the largest programme for antiretroviral drugs in the world as an example of how people from all backgrounds can work together – from medical professions to communities of people suffering from HIV/AIDS.

“It’s a very wonderful example of science and community organizations, the media, the law, coming together to produce a remarkable result,” he said. “It saved South Africa from a sense of growing despair. Now there’s hope in that country and we have to thank the scientists as much as anybody else for making that possible.”

But, he added, there is even a tension within the very concept of sustainable development itself.

“With so much poverty and hunger is it right to be worried about future issues of the planet and the world? Is it right to spend money on art and beautiful buildings and the Constitutional Court?” he said. “Surely all the poor want is enough food and protection.”

When this issue rises, he said, he thinks of Mrs. Grootboom and her court case. He thinks of how she was in line for years for a dignified home but died before she could receive one. Then he considers her children and says he’s glad she was at the centre of that kind of debate, because people should think about the right of people who survive on almost nothing to be a part of the tensions that shape their lives. And from there, his conclusion was easy.

"You don’t have to be white to be green. You don't have to be black to be green. You don't have to be brown to be green. You don't hae to be yellow to be green," he said. “You have to be human to be green.

“Is it right to say, because they want a roof over their heads and they want a full stomach, they’re not interested in the future of the planet? Or are we depriving them of imagination? Of hope?” he pointedly asked. “Of the children thinking that the only thing that matters is not to starve and to be protected from that rain? That ideas don’t matter? That beauty doesn’t matter? That culture doesn’t matter?”

Sean Treacy