Pomegranates have sometimes had an important presence in history. King Henry VIII of England and his wife Catherine of Aragon had the pomegranate of Granada in their emblem, and the pioneering artist Pablo Picasso depicted them in paintings. Pomegranates exert a certain fascination for people in science, too. In recent times, studies proved that it is rich in useful bioactive compounds – more than 120 in all – that are good for human health.

Not only does pomegranate contains antioxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-microbial compounds. It also finds applications as animal feed, as natural dye and for nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals. South Africa in particular is expanding its pomegranate cultivation, especially in the Western Cape and Northern Cape. Unfortunately, about 30% of the harvest is sunburned, and that means the fruit cannot be eaten, juiced for drinking or used for other purposes. Usually those damaged fruits are thrown away.

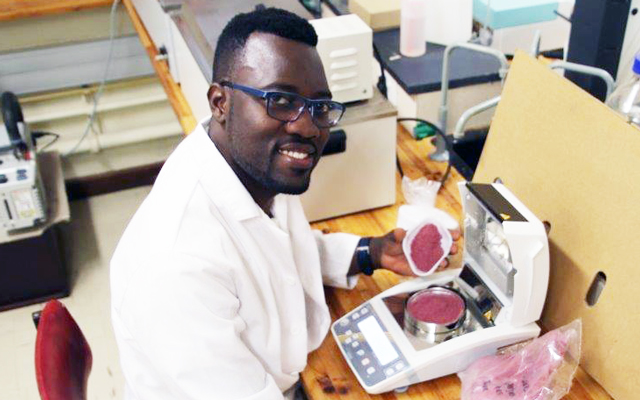

"I developed an interest in pomegranates during the years of my PhD under the supervision of professor Opara at the South African Research Chair in Postharvest Technology, Stellenbosch University (SU),” explained Olaniyi Fawole, during his presentation at TWAS's General Meeting in Rwanda. Fawole, who is a researcher in postharvest technology at the university, added: "When I started my investigations on pomegranate I found that it contains substances with good pharmacological properties."

Fawole was elected as a Young Affiliate in 2016, and presented his results on 17 November, during the session dedicated to TWAS's Young Affiliates, along with other 12 scientists from the same group.

Young Affiliates are elected to TWAS for a five-year tenure. They have excellent scientific curricula with at least ten international publications in peer-reviewed journals. They are invited to attend TWAS's General Meetings as observers, and are encouraged to provide feedback to the Academy on how it can respond to the needs of young scientists in developing countries.

Fawole is also a founding member of the recently founded TWAS Young Affiliate Network (TYAN). He earned a bachelor's degree at Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria and a master's at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, in South Africa. After PhD work from 2010-2013 at Stellenbosch University, he received the prestigious Claude Leon Foundation award to pursue a postdoctoral study at SU from 2013 to 2015.

His work is aimed at determining optimum fruit maturity and postharvest handling protocols, which help maintain quality and reduce losses during postharvest handling and marketing. What baffled him, in fact, was the high percentage of fruits that cannot be marketed because the strong South African Sun burns their skin.

Sunburn bleaches the typical red colour of pomegranate arils (the inner red seeds), a term commonly known as “cooking effect” by farmers. This renders the fruit undesirable for processing into other products, Fawole explained. Disposal of unsold fruits stresses the environment.

Globally, pomegranates are currently the 18th most consumed fruit, and demand is expected to grow. Domestication of pomegranate occurred in Asia nearly 4,000 years ago, in the Afghanistan area where these fruits have adjusted to becoming heat-resistant, with optimal maturation in the range of 25-30°C. Cultivation has spread worldwide and now pomegranates are grown in more than 35 countries, including India, Israel, Tunisia, Peru, Iran and Turkey. South Africa, with about 1,000 hectares in cultivation, is becoming a major producer and global competitor.

"I felt I had to do something to help maintain the competitiveness of this emerging industry in South Africa," Fawole recalled. He decided to explore the hidden potential of pomegranates that get discarded. He focused, in particular, on their seeds' oil, and its potential properties and use. Among over 1,000 cultivars identified so far, Fawole chose one called ‘Wonderful’, which is popular in South Africa. Using sophisticated chemical procedures, Fawole extracted the oils and worked to identify new biological properties. He compared oils extracted from sunburned fruit and healthy fruit.

"I was glad to see that sunburned fruit were still potentially useful," he explained. "The oil obtained from their seeds has interesting antibacterial activity against many common bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli." But it is also rich in molecules with that get rid of free radicals and tyrosinase-inhibition activity (tyrosinase is an enzyme involved in pigmentation). As a next step, Fawole wants to optimise the processing technique and patent his results and ultimately launch a spin-off company within the industry to expand the exploitation of this unexpected resource.

Cristina Serra