A preventive vaccine against Plasmodium could, of course, decrease the incidence of the disease.

A preventive vaccine against Plasmodium could, of course, decrease the incidence of the disease.

Yet, despite years of studies, there are few signs that researchers are on the brink of finding a vaccine. That's why a successful strategy designed to contain the Plasmodium and curb the symptoms of the disease would be welcome. In effect, it would buy time for scientists to come up with an effective vaccine.

Ricardo Gazzinelli, professor at the Department of Biochemistry and Immunology at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) and winner of the 2009 TWAS prize in the medical sciences, has focused much of his research on devising what he calls a "buffer strategy" designed to ease the health burden that malaria currently exerts on the world's poorest and most vulnerable people.

"I've always been fascinated by the ability of intracellular parasites to escape the surveillance of our immune system," says Gazzinelli, who has studied the impact of parasitic diseases in developing countries for more than 15 years.

Gazzinelli, who was born in New York City, has lived most of his life in Brazil. He earned all three of his university degrees at UFMG, including a doctorate in biochemistry and immunology.

Following a post-doctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health in the US, Gazzinelli returned to Brazil in 1995 to become a professor of biochemistry and immunology at UFMG.

Gazzinelli lives and works in Minas Gerais in southeastern Brazil, where parasitic diseases are a significant health burden. Malaria alone affects more than 500,000 people in Brazil each year. The Anopheles darlingi mosquito causes most cases.

Gazzinelli is widely recognized as Brazil's leading researcher in the study of parasitic diseases. He specializes in studies examining the role that innate immunity plays in the incidence of malaria. He founded both the Laboratory of Immunoparasitology at UFMG and the Laboratory of Immunopathology at Centro de Pesquisas René Rachou.

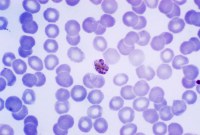

"Plasmodium residing in red blood cells sets the stage for malaria," say Gazzinelli. "Yet many incidences are actually triggered by a host immune response, which leads to acute inflammation."

Gazzinelli and his research team have shown that adverse reactions to the parasite are set in motion by a family of receptors, called TLRs or toll-like receptors, anchored to the membrane of the immune cells. "The parasite binds to these receptors. When the immune cells recognize the parasite, the receptors release inflammatory substances called cytokines. This intensifies the inflammation, worsening the clinical outcome".

Gazzinelli and his fellow researchers hypothesized that inhibiting the activation of the receptors would impede the release of inflammatory substances and therefore reduce the inflammation. Specifically, they have created a synthetic molecule, E6446, that binds to the target receptor and thus inhibit its activation. Experimental tests to date have shown promising results.

"This strategy could help reduce the incidence of malaria mortality until scientists are able to develop a preventive vaccine," says Gazzinelli.

Yet, he is by no means content to create a successful stopgap measure and leave it at that. Gazzinelli led efforts to launch Brazil's National Institute of Science and Technology in Vaccines, which is currently testing innovative technologies for vaccines to combat malaria and other neglected diseases.