If you want to fight mosquitoes that spread malaria, you have to understand the mosquito lifestyle. Where do they go to breed? Where do their young flourish and grow strong? How do these habitats come to exist?

These are questions that Kenyan entomologist Joseph Mwangangi seeks to answer with his research. “Life in water determines the body size of a mosquito,” said Mwangangi. “This is important, in that bigger mosquitoes are more healthy. They can survive and transmit the disease more.”

To understand which pools of water create the healthiest mosquitoes Mwangangi needed mosquito-rearing chambers – cases in which he could simulate environments where mosquitoes breed. But he needed financial help to get the chambers. And in 2010, he got it, through a research grant from TWAS.

Across the regions of the world where people are most vulnerable to the world’s most devastating diseases, local research is an essential part of the battle. TWAS research grants have been an important part of this effort, helping scientists throughout the developing world acquire the funding they need to establish labs, invigorate research careers and make key discoveries.

Across the regions of the world where people are most vulnerable to the world’s most devastating diseases, local research is an essential part of the battle. TWAS research grants have been an important part of this effort, helping scientists throughout the developing world acquire the funding they need to establish labs, invigorate research careers and make key discoveries.

Much of this work in epidemiology and medicine was on display at the TWAS Research Grants Conference held in Trieste, Italy, from 18-22 April, attended by over 40 scientists from 26 developing countries who were past recipients of a TWAS grant. The conference highlighted the work done by TWAS research grantees like Mwangangi, helping uncover needed information on some of the world’s harshest diseases, including malaria, HIV, hepititis and Hodgkin’s lynphoma.

Since the programme's start in 1986, TWAS has awarded more than 2,300 grants totaling USD 16.6 million. Funding provided by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) became the core of the programme in 1991. A separate grant programme, funded by COMSTECH and TWAS, is open to young scientists from member countries of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

Fighting malaria with local science

Among Mwangangi’s findings was that 90% of the malaria mosquitoes in Kenya breed in still pools created by human beings, such as unfilled holes left behind from construction and abandoned swimming pools. This is indispensable information, because it helps the government prioritize measures to keep the insects under control.

“TWAS, to me, was like a seed grant, which enabled us to build a fundamental group in vector biology,” he said. “The Ministry of Health looks to us for information now on adult mosquitoes.”

“TWAS, to me, was like a seed grant, which enabled us to build a fundamental group in vector biology,” he said. “The Ministry of Health looks to us for information now on adult mosquitoes.”

Malaria is one of the developing world’s most deadly epidemics, killing over a million people every year, most of them children in Africa. Robust research in labs and in the field in developing countries is an essential part of saving lives.

Malaria researcher Luna Kamau, also of Kenya, received a TWAS grant in 2007 to research whether a new mosquito species in the region was a malaria threat. That research was inconclusive, but the grant signaled a time of change for her malaria lab. Her publication rate and funding climbed, and she is actively training many more scientists to tackle epidemiological problems. Of the 25 students she has trained in her career, 20 came to her after she received the TWAS grant, including all eight of her PhD students.

“You’re considered more eligible to pick up students because they perceive you as a good researcher,” she said. “Directly, the grant drew students to me.”

Homegrown science is important, she said, because scientists in the country with an epidemic like malaria can understand the gravity and nature of the problem first-hand. “More often than not we have gotten the problem ourselves,” she said.

TWAS is also supporting research where malaria is on its last legs and the emphasis is on elimination, such as Ecuador. Infectious disease researcher Fabian Saenz said the grant he received in 2013 opened up a new field of research in Ecuador, looking for variations in how the malaria parasite get into red blood cells.

TWAS is also supporting research where malaria is on its last legs and the emphasis is on elimination, such as Ecuador. Infectious disease researcher Fabian Saenz said the grant he received in 2013 opened up a new field of research in Ecuador, looking for variations in how the malaria parasite get into red blood cells.

Normally, people have a molecule called a “receptor” on the surfaces of their red blood cells that acts as a gateway to one kind of malaria. “When people don’t have the receptor, they can’t get that type of malaria,” he said. “But Ecuador appears to be the first place on the Pacific Coast of South America where we see that some people have this parasite but don’t have the receptor.”

"This pattern has been seen before in Africa and other parts of the world", he said, but the malaria parasite’s method for getting in could be different in Latin America. So they need to research the issue locally. The prestige of receiving an international grant has also given Saenz’s lab a new level of credibility, opening the door for them to work with Ecuador’s Ministry of Public Health as well as international organizations.

“It's the opportunity to make a difference and be able to help people in need," he said. "Basically, you are where people need you, and working with people in the field.”

More minds means stronger medicine

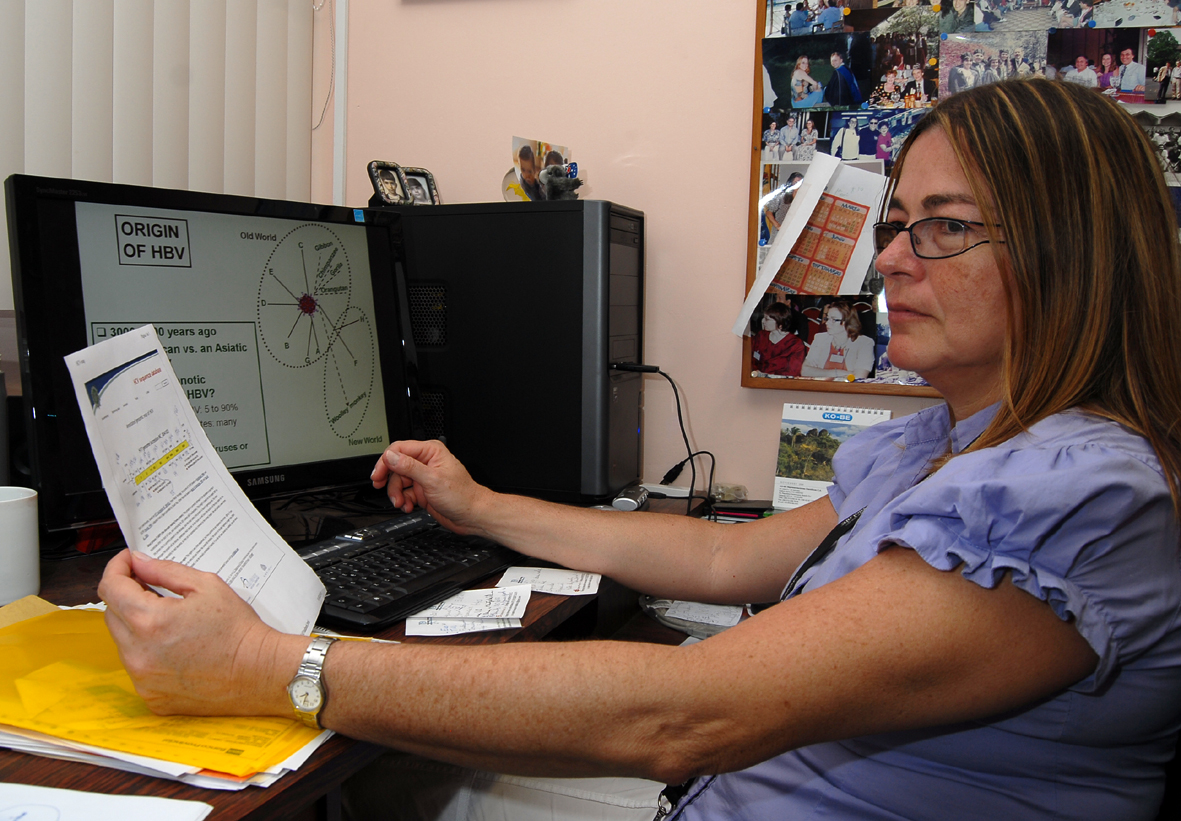

Microbiologist Flor Pujol of Venezuela is the head of a virology lab. She got her first TWAS grant in the late 1990s, which gave her career a boost and helped her create a new molecular virology lab in 2002.

Microbiologist Flor Pujol of Venezuela is the head of a virology lab. She got her first TWAS grant in the late 1990s, which gave her career a boost and helped her create a new molecular virology lab in 2002.

She said funding from TWAS was a career-driver for several Venezuelan scientists. By supporting her work over 15 years ago, she was able to train local scientists in virology in her home country. Now there is a stronger corps of virologists that can respond to outbreaks, all of whom are needed at the moment to diagnose the Zika virus and determine ways to slow its spread.

“It helped me to get more confident in applying for international grants. It helped me to acquire graduate students,” said Pujol. “We now have more minds working on the Zika problem.”

The grant also helped Venezuela develop methods for diagnosing contagious viruses, such as bloodtests. This in turn helps track how diseases in the region change to develop resistance to treatment, which also helps control their spread. Her focus is on hepatitis B and C, as well as HIV.

“We have a tight relationship between patients and data,” she said.

“We have a tight relationship between patients and data,” she said.

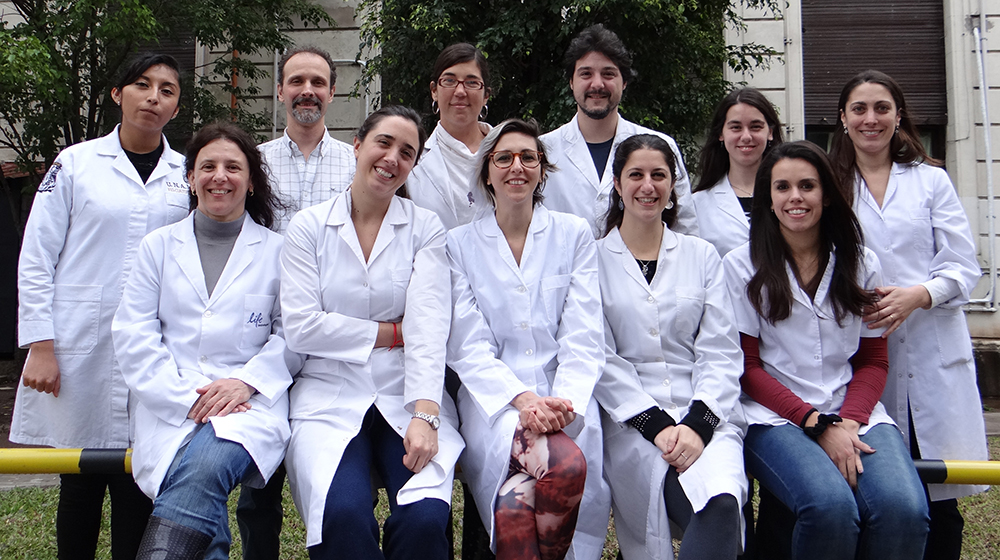

The medical field is unique in a sense because devices provided by TWAS can be directly useful to sick people in need of advanced medical technology. Such is the case for pediatric medicine researcher Maria Victoria Preciado of Argentina. Her research focuses on the Epstein-Barr virus, which carries a high risk of a kind of blood cancer called lymphoma.

Preciado received a grant in 1997 for equipment to support the molecular analysis of tissues that could contain the virus, which is not only useful to research but can literally be a matter of life or death for transplant patients. Her team was the first to develop a technique called in situ hybridization in Argentina, which is a way to detect Epstein-Barr in tissue samples. Doctors and researchers can now look for the disease in the tissues of organs of transplant patients with weakened immune systems.

“Normally people can live with the Epstein-Barr virus in a steady state because the immune system controls the virus,” she explained. “But when you are immunocompromised, the virus can multiply without stop.”

“We can now have high technology for diagnosis of rare diseases,” Preciado said. “It’s important for hospitals to have this.”

Sean Treacy