You cannot develop people, you must allow people to develop themselves. One way to accomplish this is through education, which is also a good way to fight poverty and promote growth.

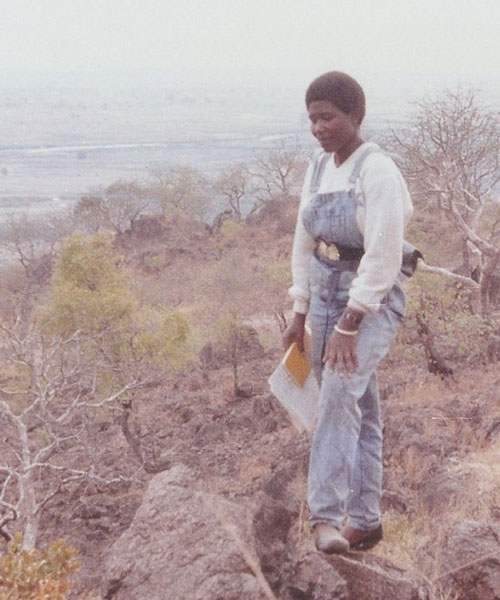

These inspiring ideas were expressed by Julius K. Nyerere, who served as president of Tanzania from 1964 until 1985, and they are the guiding star today for Tanzanian Earth scientist Evelyne Mbede, a 2013 TWAS Fellow. An influential advocate for research, Mbede is credited with being in the leadership of STI during the period when there was a 30-fold increase in government funding for science.

"During the almost ten years that I spent working for the Tanzanian government, I exchanged experiences with men and women from various countries," she said. "That opened a window on the importance on how to motivate people, especially women, to go back to school and take a scientific career."

A native of Njombe, Tanzania, Mbede established strong credentials for research in basin tectonics and earthquake risks, and for connecting the work to communities in those zones. She served as the director of science and technology in the Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology from 2007 to January 2017. She is a member of the Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD) and a fellow of the Tanzania Academy of Sciences.

She earned her PhD in 1993 from the Technical University Berlin. Later she served as the dean of the current College of Natural and Applied Sciences at the University of Dar es Salaam and was chairperson for of the International Commission of Earth Scientists in Africa (ICESA).

"I decided to dedicate my life to science during my childhood," she recalls. "My father was a primary school teacher. We used to listen to BBC programmes and read scientific and geographical magazines. It was then that I started thinking that I should be able to go to a scientific university."

Working for Tanzania

Thanks to her father, Mbede was guided to take advantage of education opportunities offered to women in Tanzania. About 66.3% women scientists, in fact, still experience the influence of the gender bias in their participation in Science, Engineering and Technology industry. But her father's open mind gave Mbede better chances for herself, and to make a difference for Tanzania.

Tanzania is among the United Nations list of 47 Least Developed Countries, which are included in a longer list of 66 nations that TWAS has identified as lagging in science and technology.

Talking about Tanzanian women scientists, Mbede mentioned the importance that her affiliation to OWSD had during her political activity. "I joined OWSD very early after my PhD, and that gave me the opportunity to establish good interactions with women from East African countries."

Also working for the government, in the policy-making section first, and then her affiliation to TWAS were two very important steps. "For me, the window to interact with people increased a lot." According to Mbede's experience, Tanzanian women who succeed in science eventually experience good careers. The problem, she observed, is in the starting numbers. "The percentage of women in biological sciences is fairly good," she said, "but when it comes to physical sciences, the problem becomes bigger."

Higher education statistics show that despite a moderate increase in enrolment in universities and colleges during the last ten years, the percentage of women in science remains limited to approximately 30%. And this divergence increases even more in higher education and policy-making positions.

"During my ministerial mandate I struggled to fill more positions and get equal opportunities for women," she recalled. "And I urged policymakers on the importance of having scientists in the decision-making processes, because if we leave non-experts to decide on our behalf, the risk is that these people do not understand why they should invest funds in one activity rather than in another."

Before moving to the realm of policy, Mbede was a very active scientist, working on volcanic zones, taking geological prospects, monitoring earthquakes and offering advice to communities living in seismically active areas of Northern Tanzania. In addition, she was often engaged in discussions related to the environment, also at international events.

Back to field science

Today, after her experience at the Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology, Mbede is working as an associate professor in Earth sciences at the University of Dar es Salaam.

Her political and scientific experience have broadened her perspective on how Tanzania should use its scientific workforce, both locally and internationally: by building teamwork.

"The seismology unit of our department is part of a wider team including the minister of energy and other groups," she explained. "We are involved in advising the government about the seismic risk.

"But we also do continuous training for people who live in highly tectonic areas, like the Rungwe Mountains. After a seismic event, we rush to the earthquake-stricken area to make sure that people are not affected by aftershock."

Nobody can stop eruptions, but preparedness is a must. Reports of early 2017, on the signs that an eruptions was imminent at Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano in northeastern Tanzania, also known as the “Mountain of God”. "The seismology unit at UDSM is ready to move quickly and mobile stations to monitor its activity closely," through government facilitation under the coordination of the Commission for Science and Technology."

International collaborations are an important part of Evelyne Mbede's research activity and her work with the government has brought her close to science diplomacy initiatives. "Tanzania is in the core of Africa," she explained, "so we share some problems with other nations and we also need to consult with foreign affairs cabinets, foreign ministries, UN agencies and a global, international environment."

Finding financial support for research was not difficult in Tanzania. "During the 10 years I spent working for the government, Tanzania gave a substantial amount of funding for research," she recalled. "When I arrived there, in 2007, the budget for research was less than one billion Tanzanian shillings, but...it has been increased up to 30 billion shillings."

With an eye to the future, the Tanzanian government is now allocating funds not only for research, but also for human resource capacity development. Increasing research capacity is part of the national agenda: funding now goes into human resources, for postgraduate fellowships, and also into mobilizing research and laboratories, offering Tanzanian scientists a better research environment.

"We also receive funds from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), and support from the Dutch organisation for internationalisation in education (NUFFIC), as well as from various international research funding agencies," Mbede acknowledged.

Regarding her scientific career, she noted: "At the time I was elected to TWAS I was in the government, hence I didn't have enough time to do research." Still, even as she returns to research, one thing certainly won't change: Evelyne Mbede is committed to science as a form of public service, and to having a positive impact.

Cristina Serra