Climate change poses a threat to the far-flung islands of Kiribati in the Central Pacific: Storms are turning strangely unpredictable. Temperatures that have been stable for millennia in the ocean, on land and in the atmosphere are rising. And the seas are rising around atolls that rest just above sea level. For more than 100,000 residents, an ancient culture – and their way of life – is at risk.

But in a filmed interview with The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS), Kiribati diplomat Christine Greene offers a cautiously optimistic vision in which the island republic develops innovative solutions by drawing from both indigenous knowledge and the latest research, and by working with international partners.

"The sea levels are rising," says Greene, Kiribati's honourary consul to the United States. "But are we saying goodbye to Kiribati? No – I don't believe so. With the collective science and that data that is now available, with all of the technology that is available, it doesn't look like we're going to be saying goodbye to Kiribati.

"Rather, perhaps we will be welcoming a new aqueous nation."

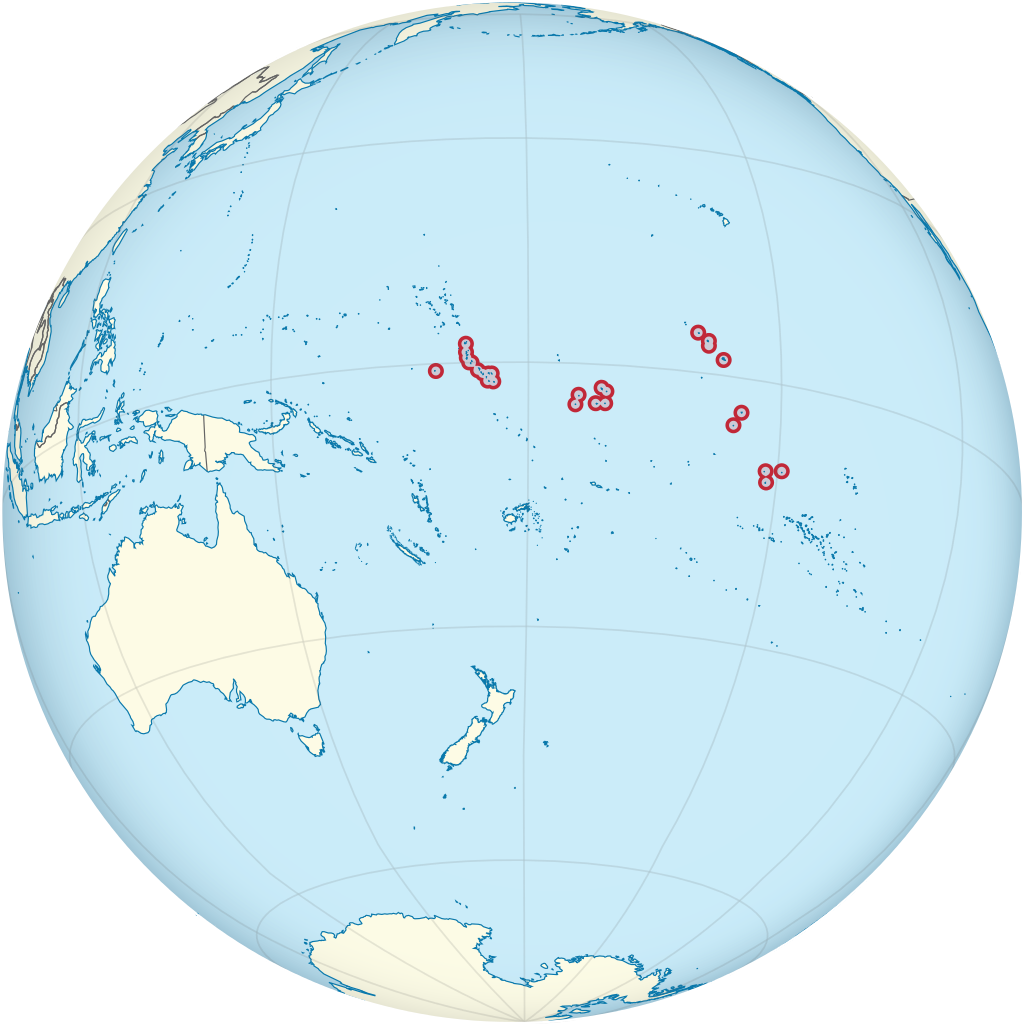

Kiribati (pronounced KEER-ih-bahss) is a central Pacific republic comprised of 34 islands, mostly ring-shaped atolls which sit about a metre above sea level. The islands are scattered across some 4,800 kilometres (3,000 miles) from west to east, extending into all four hemispheres. The United Nations has designated Kiribati as one of the world's 47 Least Developed Nations, and as such it qualifies for many TWAS programmes[link: https://twas.org/opportunities] to build science capacity.

Kiribati (pronounced KEER-ih-bahss) is a central Pacific republic comprised of 34 islands, mostly ring-shaped atolls which sit about a metre above sea level. The islands are scattered across some 4,800 kilometres (3,000 miles) from west to east, extending into all four hemispheres. The United Nations has designated Kiribati as one of the world's 47 Least Developed Nations, and as such it qualifies for many TWAS programmes[link: https://twas.org/opportunities] to build science capacity.

In a later interview, Greene expanded on her idea of an "aqueous nation". By that, she means a nation that already is made up almost entirely of ocean "will adapt and even prosper as the climate system shifts around us."

She added: "It is important to remember that Kiribati, along with our neighbour Tuvalu, has the highest percentage of ocean that is part of our sovereign territory than any other nation on the planet – over 99%. This, I believe, is to our advantage in an age when the value of the ocean is finally being recognized through the provision of food through fish; essential deep-sea metals collected in an environmentally responsible way for the world's transition of a low-carbon energy future; and the many other assets the ocean has to offer.

"One encouraging example is the recent discovery of what scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (USA) are calling 'super reefs'. These are reef systems in Kiribati that are naturally resilient to heating and may offer promise of our reefs, and thus our islands, surviving in a hotter world even with rapidly rising sea levels.

"Are we out of the woods? No, but there is hope."

Worldwide, warming temperatures cause ocean waters to expand, and that's a key driver in sea-level rise. For Kiribati, Green says, only 30-50 years remain before the changing climate will usher in a new age. But in such a traditional and isolated culture, people will never abandon their ancestral land. And in any case, "there's nowhere to run," she added. "So we will stay, we will prosper and we will adapt."

In the new short film, Greene explores the climate-related threats confronting Kiribati, the essential role of science in providing innovative solutions, and the urgent need for developed nations – and their scientists – to work with Kiribati. Her intriguing perspective is likely to resonate with other threatened island nations, from the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific to the tropical Maldives below India to the coastal islands of the Chukchi Sea off of Arctic Alaska.

The film was directed by Nicole Leghissa, who has worked with TWAS on a number of other films, including "Science in Exile"[link: https://twas.org/science-exile] (2017), which explores the challenges confronting researchers displaced by war.

The interview with Greene was filmed in Trieste, Italy, during the science diplomacy course[link: https://twas.org/science-diplomacy] organised annually by TWAS and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Also speaking at that event[link: https://twas.org/article/vanishing-country] was Greg Stone, chief scientist and executive vice president at Conservation International as well as science adviser to the government of Kiribati.

In recent years, Greene said, awareness about climate change and other environmental issues has grown. Today, the nation has a leadership role in managing and protecting the surrounding Pacific spawning grounds for various sorts of tuna that are consumed around the world.

Now, however, the people of Kiribati and their allies must protect their own culture. Greene envisions atolls built up to stay above the rising seas; architectural proposals for floating islands, which seemed outlandish just a decade ago, now are attracting close attention, she says.

"We're custodians of one of the most important endowments on the planet today," she says. "To help us maintain that pristine area, we need access to all of the science."

Edward W. Lempinen