The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics is already a core institution for physics and mathematics in the developing world. Now, as it gets ready to begin its second half-century, the centre is expanding into areas that seem to extend well beyond theoretical: how physics intertwines with the life sciences, for example, and more applied research in areas such as telecommunications and renewable energy.

The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics is already a core institution for physics and mathematics in the developing world. Now, as it gets ready to begin its second half-century, the centre is expanding into areas that seem to extend well beyond theoretical: how physics intertwines with the life sciences, for example, and more applied research in areas such as telecommunications and renewable energy.

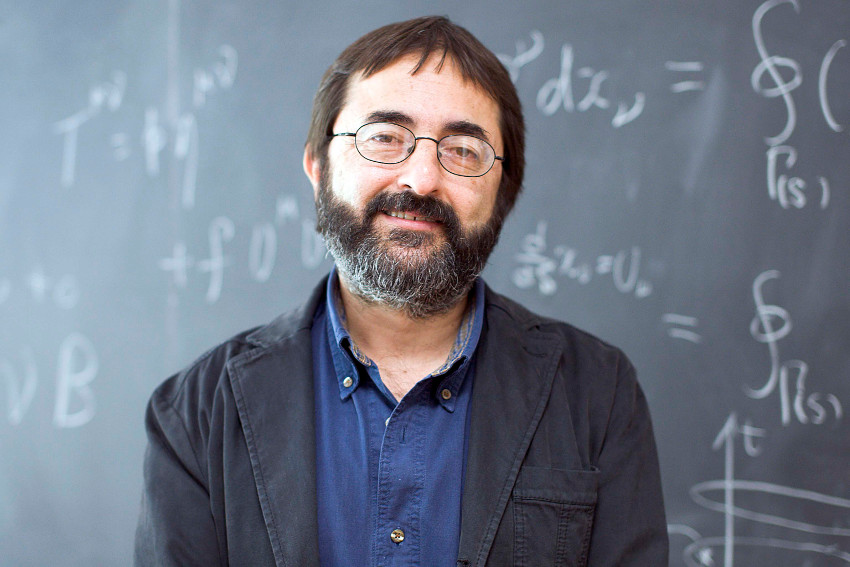

Add in a new network of satellite centres throughout the developing world, and it’s clear that ICTP is looking to extend its networks – and strengthen its influence – in whole new ways, says Director Fernando Quevedo.

Quevedo was appointed director in 2009. Born in Costa Rica and a citizen of Guatemala, he is a highly regarded particle physicist and has been honoured for his contributions to superstring theory, a broad effort to bind together all of the universe’s most fundamental particles and forces into a single model. He has also been a TWAS Fellow since 2010, and ICTP has a long history with TWAS – both were founded by Nobel laureate Abdus Salam, and ICTP hosts the Academy’s offices on its campus in Trieste, Italy.

ICTP is planning to celebrate its milestone anniversary with a four-day event in October that will draw everyone from Nobel laureates to the most promising young scientific minds in the developing world. With preparations underway for the celebration, Sean Treacy from the TWAS Public Information Office interviewed Quevedo to discuss the centre’s past and future.

What are ICTP’s greatest achievements over the past 50 years?

We always say that ICTP is an institution run by scientists for scientists. The achievements are how much we have helped scientists to keep on with their careers, their research, and advocate for future generations. The fact that we have a big network of scientists who have trained here, and who have sent us their students who are doing activities with us through several generations, is exactly what we think the mission of ICTP has been.

We always say that ICTP is an institution run by scientists for scientists. The achievements are how much we have helped scientists to keep on with their careers, their research, and advocate for future generations. The fact that we have a big network of scientists who have trained here, and who have sent us their students who are doing activities with us through several generations, is exactly what we think the mission of ICTP has been.

The only way to promote science as a long-term project is to measure in human resources. The fact that there are people doing science, in particular physics and mathematics, in developing countries over these 50 years, that has been an achievement of ICTP. Otherwise these people would have left the field or the country. So in that sense we have been working against brain drain and have managed to keep this community of scientists active. That is overall our main achievement.

Could you tell me a few examples of people who came to ICTP and went on to help control the brain drain problem?

Brain drain is a very delicate issue. We want to have high level science in developing countries, for this they [the countries] need to support the scientists. But sometimes policy makers tend to treat the scientists as objects. They may not realize that the most important component in the scientific activities are the scientists themselves and that we became scientists because we fell in love with the field itself and decided to dedicate our whole lives to that. ICTP supports scientists and helps to fight the brain drain but it is up to their countries to recognise their value and offer them good conditions to go back.

There are some success cases we had who didn’t go back to their countries. There is one particular diploma student from Venezuela, Freddy Cachazo. He is now a professor at Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (in Waterloo, Canada), one of the top institutions in the world. He won the New Horizons in Physics Prize, which is one of the new big prizes. You cannot deny it’s a success story because he was trained at ICTP. Without ICTP he couldn’t have done all that. And now he’s contributed to science at the top level. So in a sense you can see the mission of ICTP is supporting these scientists from developing countries. This didn’t lead directly to him going back to his country and doing science there. On the other hand, as a role model, he has been helping people in developing countries. We have activities, we ask him to help, and he’s always active. So in that sense, it’s not a loss for the developing countries and he is contributing to world science.

It can be said too many have left developing countries in the past, and gone to the United States or Europe, but then they can go back [to their home countries] do research and teach. So this diaspora is not a complete loss for the country. In my experience, I’m a case of brain drain, because I left my country and didn’t go back. But the reason I’m here at ICTP is I’m trying to support developing countries, because I know there are many people like me who want to become scientists but are not given those opportunities.

There are other examples of successful ICTP alumni who went back to their countries. One student, Shaaban Khalil, he was our diploma student, he was from Egypt, we trained him here, helped him get a PhD position in a European country, he came back to ICTP as a postdoc. Then, following the advice of ICTP staff members, he decided to go back to Egypt. So he went back, we supported him there, he sent us his own students and helped organize activities with us. He became the founder of what we call the affiliated centre for ICTP (we have seven or so affiliated centres in the world), the Centre for Theoretical Physics first at the British University in Egypt and now moved to be the first (of more than 10) centers of the newly created Zewail City of Science (the most ambitious scientific initiative in Egypt) and has joined the CMS experiment at CERN, one of the two experiments that discovered the Higgs particle two years ago.

So, in just one single person, you can see how ICTP has helped different people in their career, all the way to going back to their original country.

We’re also able to say we’ve had visitors from essentially every single country in the world, all 188 countries. That makes us unique.

How do you reach out to policymakers in those developing countries and help them improve their conditions for science?

Some of the people attached to ICTP have been major scientists in their own countries, so they have access to ministers of science and so on. So we can reach through that level. They’re a big part of the scientific community, and they were trained or educated at ICTP at some point in their lives, so they know about ICTP. It is wonderful to go to India, Iran and Brazil for instance, and meet scientists, at all different points in their careers, that talk about how ICTP was important for them. And we can continue to work with them and they will support our work.

What does it mean for ICTP to be 50 years old and still going strong?

Just surviving is not trivial. The fact that the original dream of Abdus Salam, of having top scientific research for scientists from developing countries, proved to be a real visionary idea. At that time, I think this global vision was probably not appreciated by many other people because it was in the middle of the Cold War and countries were in very bad shape, particularly developing countries. But we can see that it made a big difference. So we are proud. We’re also able to say we’ve had visitors from essentially every single country in the world, all 188 countries. That makes us unique. So we’re thankful, not only for Abdus Salam’s work but all other founders and the previous directors of ICTP. Just keeping this mission working is not a trivial task.

Where do you see ICTP 50 years from now? Feel free to indulge your imagination.

(Laughs) Yes, that’s good. Well, you have to expand or otherwise you become extinct. Expansion means several things.

There’s expansion in-house. We are a very small institution, and what we have proven in these 50 years is that ICTP is a good model. It has worked, and anything that doesn’t work has been eliminated – think of it as natural selection – and everything we have been doing has been successful for us. Hiring two or three times the number of scientists (would be good). Because the need is there, the challenges are there, and if you want to say anything negative about ICTP, it’s that it’s too small. The model is very good. But being small, we can detect the need, but we don’t have the resources to do everything.

So expansion, in-house, makes a lot of sense – but not only more of the same. Because also, science has developed in the last few years. It’s good to have the basic sciences that we’ve supported all this time: high energy physics and cosmology and condensed matter and pure mathematics. But the vision of Salam was also for more applied subjects – climate change, telecommunications and so on.

There are also fields emerging as basic fields. For me, I just think it’s fascinating, for example, the relationship between physics and biology or mathematics and biology – we call it quantitative biology – is something that is very fast-growing and promising to be a major player in this century, at least.

For expansion outside Trieste, we are starting new partner institutions so that they can play the same role that ICTP plays in their own region. The first successful case is in São Paulo (Brazil). We have a centre called ICTP-SAIFR (South American Institute for Fundamental Research), which is basically at the University of São Paulo funded by Brazil and São Paulo state. That’s a way in which ICTP’s mission has been expanding because we have a sister institution in Brazil that can play the same role that we play for the region close to Brazil.

One in Chiapas, Mexico, is building up; that’s to cover the region between Central America and the Caribbean. Then we are also starting one in Izmir, Turkey, to cover the region nearby. One in China, in Beijing, with the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. We’re also planning to have one with the University of Rwanda to cover probably not all of Africa, but at least East Africa. And probably more – we have possibilities in other countries.

So my vision for 50 years from now is to have a real network of ICTP-like institutions based in key countries to address the problems of those regions, because the situation near, say, Brazil is very different from the countries near Mexico.

What do ICTP and the developing world need to be a player in quantitative biology? Does it come down to computing power?

Exactly, but much more than that. And we also need scientists trained on that area. So we are creating a new research group in quantitative biology. We’ve hired the first person already, and we’re having schools and activities. This is something we’re starting and we’re hoping it will increase substantially.

People usually say this will be the century of biology, but nobody says this will be the century of biologists. Physicists and mathematicians can play a role in biology. That is the new turn, that physicists and mathematicians can play a key role in that field and it’s just starting to really explode. And you can see it in the demands and needs in developing countries – diseases and viruses can be studied in a more quantitative way, now.

Another area we are also starting is renewable energy, which is a big challenge for the world and particularly for developing countries. For computing power, that’s a tool that everybody has to have and we’re also starting a group in high-performance computing (HPC) in collaboration with SISSA. All of this is without taking anything away from the main subjects of ICTP, which have always been fundamental physics. We think those things, the pure and the more applied, should go together.

Now is probably the first time that this technology of communication is equally available worldwide. More than 70% of mobile phones are in developing countries.

How has information technology lessened the isolation of scientists and enhanced their ability to communicate with each other and preserve networks?

We had a problem once in the 1990s with a Nigerian community that wanted to come to one of our activities, and for some reason related to communication, it didn’t work. So then our scientists addressed the problem, went to Nigeria, and helped to install Internet in different universities. Talking to Nigerian scientists, it’s very inspiring, because they owe to ICTP that they have Internet access.

Recently, China donated a huge cluster of computers to Sudan. (A cluster of computers is a large group of computers that make up a single, larger computing system.) Even though we’re developing a big cluster ourselves, that Chinese cluster to Sudan is even bigger than our own cluster. But nobody in Sudan was trained to manage it and run it and so on, except for a Sudanese scientist who trained in one of our programs. So he took his education to this cluster of computers. We didn’t have the funds to donate a big cluster, China had it, but we had the human resources, the know-how.

We also have a group called “ICT for Development” dealing with that issue. What they like to say is they train the trainers, using simple kits you can build yourself to allow people to have access to wireless communications. Some regions have access to Internet, but only in the main cities. Once you go 100 miles from that, people often have no access. So they allow these people to have access through their kits and training in the schools and hospitals.

Now is probably the first time that this technology of communication is equally available worldwide. More than 70% of mobile phones are in developing countries, so we’re trying to have more of our materials available on mobile phones, because we know this is only going to get better. People will only have easier access, more smart phones, and so on.

We have to take advantage of that now. What used to be a big problem, isolation, is getting more or less solved by more access to communication.

How has ICTP’s close relationship to TWAS helped the centre flourish over the years?

We feel very close to TWAS. We see TWAS as a younger brother of sorts because we were both created by Salam, and I think the two institutions compliment each other in a nice way. With so many programs that we have in ICTP, TWAS supports conferences and projects and students and so on in developing countries covering fields we do not cover in ICTP. One way we see it, is what we cannot cover with our Office of External Activities, TWAS can cover in terms of other subjects such as chemistry, which are not within our mission.

We’ve also been hosting TWAS for many years now. We’ve been growing together, which is good.

How are you celebrating your anniversary?

We have a conference to celebrate the anniversary 6-9 October. We’re trying to bring top scientists and policy makers worldwide with activities at both levels. In particular, we have the Dirac Medal, one of the most prestigious prizes for theoretical physics, that we give every year. We plan to have many Dirac Medalists. Some of them got the Nobel Prize afterward so we’ll have several Nobel Prize winners.

Also, we plan to have ministers of science and directors of UNESCO, IAEA, CERN, secretary general of ITU, etc. It would be a good opportunity to remember the previous 50 years and to have a vision for the next, say, 50 years. In my case, I have to be more concrete and ask what we will accomplish in the five years, which corresponds with my period of leadership. (Laughs)

We’ll also take the opportunity not only to celebrate ICTP but to discuss the role of ICTP and other international institutions for the promotion of science worldwide, and how we can work together.