Globalization and the fall of internal borders among countries are turning planet Earth into a global village. By living on Earth, we all share not only commodities, cultures and traditions. We also share common emergencies such as providing future generations with enough food.

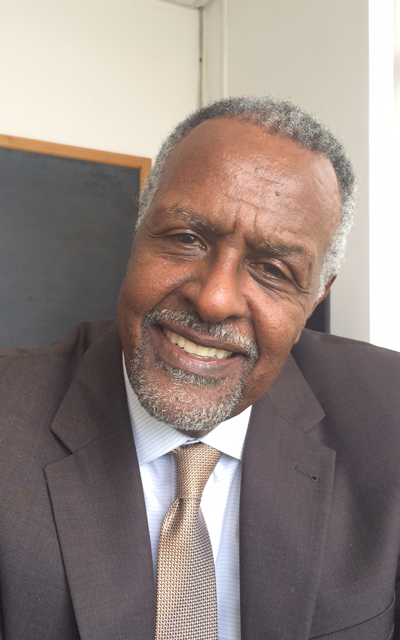

Gebisa Ejeta, a member of the UN Secretary-General's Scientific Advisory Board (UNSAB) that met in Trieste (24-25 May), is a globally recognized food expert. He grew up in the smal l Ethiopian village of Wollonkomi, and is currently a distinguished professor of agronomy at Purdue University, Indiana (US) and the executive director of the Purdue Center for Global Food Security.

l Ethiopian village of Wollonkomi, and is currently a distinguished professor of agronomy at Purdue University, Indiana (US) and the executive director of the Purdue Center for Global Food Security.

His research has addressed the genetic modification of sorghum to induce resistance to drought, striga weed, and other environmental stress. Sorghum is one of the world’s five principal grains, part of the diet of hundreds of millions of people, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Ejeta's career has also focused on training and inspiring a new generation of African agricultural scientists to follow and continue his work. He was named a US Science Envoy for Africa and special adviser to the Administrator of USAID, before being appointed by US President Barack Obama to the Board for International Food and Agricultural Development (BIFAD) in 2011.

Ejeta was in Trieste, Italy, to participate in final meeting of the UNSAB, which was established by UN Secretary general Ban Ki-moon to provide advice from leading renowned scientists, and offer recommendations on the role of science in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Ejeta chairs the board's working group on food security and health. While in Trieste, he was interviewed by TWAS staff writer Cristina Serra.

Food production and food security must be counted among the world's most urgent issues, especially given that the world population's peak is expected later in this century. Why do governments sometimes seem insensitive to this issue?

Food shortages and starvation have always been a problem for mankind – they are part of our history. Over centuries, governments and politicians have tried to find solutions, with no success. Why? Because food is not only about food supply from agriculture, it is also about human resources, knowledge, policy. Food is often available but the poor cannot have access to the food supply. Today's situation is worsened by the lack of geographical barriers. Not only do we share the planet, but we have become a truly global village and people are aware of what takes place in different parts of the world. Young men who are educated in Africa know how people live in Europe or the US, and so they have aspirations of good life. We are not as far apart as we used to be.

What should governments of rich nations and of developing countries do to address this problem?

Governments should realize that we are living on the same small planet, that we are all interdependent and need to share the available resources in a mutually beneficial way. And resources are not only goods or crops, but also knowledge, culture and local traditions.

Investing in education programmes often seems less urgent than investing in short- term plans that appear more pressing, such as epidemics or floods. What's your opinion on this?

Rich nations need to realize that investing in education, science, technology and innovation that takes place in developing countries is in their own best interest as well. It costs money today to assist these poor nations, but eventually the benefits will be for everyone: for rich nations but also for the poorest countries because a lot of the problems that follow can be avoided if people from poor nations will be given the chance to appreciate that they can have a good life in their nations and countries. This is why policymakers in poor nations should realize the value of investing in education, which creates a win-win situation. Poor nations can't continue to rely on rich nations for their needs: political decisions need to reflect their own long-term perspective on how to develop their nations.

Our economic system reflects general imbalance. We use so much land to feed cattle and farm animals instead of using fields to produce crops for everybody. What's your projection for the future?

This is an important point. The reason why there is such a high demand for proteins from meat is that emerging economies want to live as rich nations, where meat consumption is high. A problem is emerging, unfortunately in a sad way: overnutrition. People are eating a lot more, their caloric intake is higher and this is generating health problems in rich nations. As a result, the rich nations are beginning to eat less meat products to reduce the emerging health problems, and at the same time this is likely to benefit people from developing countries that need more meat for their health. Livestocks and poultry are a good source of proteins, but in general a diverse diet, with less meat, is a healthy diet. And policy makers should consider this.

Europe and the US have engaged in a vibrant debate over the need to use GMOs in agriculture to provide more good-quality food. How are GMOs perceived in Africa? Are they considered an option or rather a menace?

It's difficult to capture what African view is, because there are more people speaking for Africa than Africans themselves. I can't exactly tell what an African perspective is. However, in my view, the overall feeling towards GMOs isn't that negative. A higher percentage of educated people trust technology. Also they see to have a balanced view about the options that GMO technology provides. Biotechnology cannot solve all the problems that developing countries face, however there are some problems that require the intervention of biotechnology, and having this opportunity is extremely important.

So why these mixed feelings around them?

I think that the confusion surrounding GMOs doesn't come from scientists, but from ongoing debates in Europe and North America. Europeans in general are against GMOs and not as concerned about climate change. Americans, on the other hand are for GMOs, but the American leadership is not supporting much the issue of climate change. This, of course, shows that it is not about science: that this is more about policy and economics coming into science. And Africa is caught in the middle: Africans are not publicly declaring anything. People outside Africa are speaking on their behalf, without full knowledge.

Critics complain that GMO seeds - patented and protected by agribiotech companies - are causing big problems to farmers who need to buy them every year. What's your thinking on this aspect?

Let me tell you that the notion that agrbiotech companies sell sterile seeds is not true. Rumors come ... perhaps from the public or press. It is true that hybrid crops need to be generated every year to be highly productive. Hybrid crops are needed because they are more productive than non-hybrid crops. But if farmers want to seed their own seeds they certainly can do it: but their seeds will not be as productive as the hybrid ones that they can purchase. So it is definitely better to buy seeds every year. The rumour per se, for the way it is formulated, is absolutely false. And there is another aspect that I'd like to highlight: the private sector is not the devil. Companies have technologies that are absolutely beneficial. And giving these technologies for little price can be very productive for developing counties, and in particular for African countries.

Private companies and public academies hardly ever speak the same language: should private and public institutions learn how to work together in a more constant and productive way?

This is a problem not only in developing countries but also in developed nations, where public and private sector do not interact as much as they should. In the last century, US companies and academies have worked well together creating opportunities to collaborate, and that's where modern agribiotech has come from. Today the society has changed, and we should work to ease the process also today. We need to strengthen the capacity of young people in Africa to engage and to contribute, as we have plenty of young men and women who are trained but cannot find employment in the public sector. Private companies should create new market opportunities, so that discoveries can be made and converted into new technologies. We need to create such a mechanism where public-private partnership pursue the same goals for mutual benefit.