Now that the White House has announced its intention to restore full diplomatic relations with Cuba, many U.S. scientists are eager to visit and collaborate with their Cuban counterparts. But, it takes time and patience to build the trust that is necessary to nurture these partnerships for the long term, said Sergio Jorge Pastrana, foreign secretary and executive director of the Academy of Sciences of Cuba.

"If you just have a couple conferences, people come and go," he said in an interview during the AAAS conference "Science Diplomacy 2015: Scientific Drivers for Diplomacy" in Washington D.C. "Everybody wants to go to Cuba right now…But the idea is to find a way to support this [interest] in the long run, and that is what will really make a difference for productive scientific results," he said.

The importance of trust and relationship building was echoed by speakers throughout the 29 April conference. The day-long event was organized by the AAAS Center for Science Diplomacy and drew more than 200 people, including representatives from the U.S. State Department and other federal agencies, as well as leaders from UNESCO and The World Academy of Sciences in Trieste, Italy, and the Costa Rican ambassador to the United States. Sessions at the conference covered cooperation during political strain, the roles of institutions and networks, working with shared resources, and issues in earth and environmental sciences, biology and health, and physics.

"Benefits That Go Beyond Scientific Research"

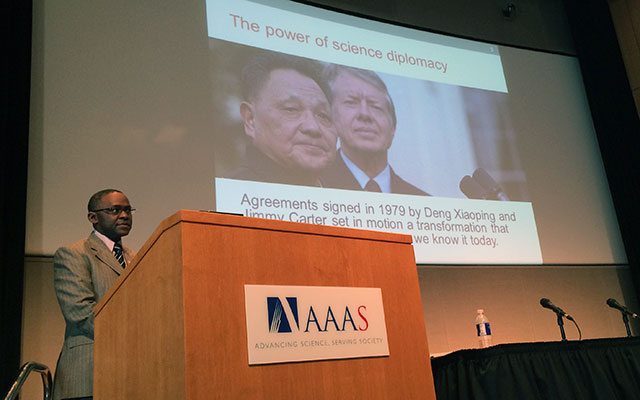

In a plenary address that opened the conference, Rush Holt, AAAS CEO and executive publisher of the Science family of journals, traced highlights in the recent history of science diplomacy, beginning with cooperation by U.S. and Soviet scientists. Their participation in talks on nuclear disarmament and in the Apollo-Soyuz space exploration project helped to establish the détente between the two nations in the 1970s, Holt said.

More recently, last month's negotiations on a nuclear deal with Iran also depended critically on science, Holt noted. Two of the key negotiators, U.S. Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz and Atomic Energy Organization of Iran head Ali Akbar Salehi, had earned doctorates in theoretical physics and nuclear engineering, respectively, from top U.S. universities and were able to talk directly with each other about the technical details of the agreement.

"There is a lot that we can do, and that we have to do, to show that the principles of science — transparency, open communication, and evidence-based thinking — go a long way to diffusing difficult situations, breaking through barriers, and developing relationships that can yield benefits that go beyond the scientific research that might be discussed," Holt said.

TWAS Executive Director Romain Murenzi also considered the past during his presentation, emphasizing that history has created not only a science gap between South and North, but also a gap of trust. Science diplomacy can be a crucial instrument in closing both gaps, he said.

"But for science diplomacy to flourish, nations must cultivate science diplomacy relationships that are balanced and fair," he suggested. While developing and developed nations must cooperate to build capacity, richer nations must respect the need of developing nations for self-determination. Toward that goal, research partnerships should be as equal as possible, with shared benefits, he said.

Flavia Schlegel, assistant director-general for the natural sciences at UNESCO, urged participants to consider issues of representation and balance in science more broadly. "I think a b ig overlying topic is science governance," she said. "Who is actually shaping the global science agenda? Who sits at the table to define what research should be done on global public goods?" she said in a plenary address.

ig overlying topic is science governance," she said. "Who is actually shaping the global science agenda? Who sits at the table to define what research should be done on global public goods?" she said in a plenary address.

Persistence and "Tensive Science"

For geologists like James Hammond, a research fellow at Imperial College London and a co-panelist with Pastrana in the session on science and political strain, some of the most interesting volcanoes lie in countries that are in conflict with their neighbors or the international community. He has studied Mt. Paektu, between China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), and Nabro Volcano, between Eritrea and Ethiopia. "Volcanoes make good natural borders, so that complicates things," Hammond joked.

In 2011, after four years of unusually strong seismic activity around Mt. Paektu, DPRK scientists sought international colleagues to help them determine the volcano's current state and its potential for an eruption. (Mt. Paektu's last eruption, in the 10th century A.D., was one of the world's largest in the last 10,000 years.) Through an arrangement facilitated by two nongovernmental organizations in North Korea and China with help from journalist Richard Stone at Science, Hammond and his colleague Clive Oppenheimer became the first Western scientists to visit the DPRK's volcano observatory, and a historic partnership was launched.

Some of the most difficult obstacles to this collaboration arose in the West, as Hammond and Oppenheimer sought government permission to ship their instruments to the DPRK, and university administrators debated signing a memorandum of understanding with the North Koreans. Ultimately, the U.K.'s Royal Society and the two Asian NGOs signed on behalf of the researchers. "It's about being very flexible," Hammond said, as well as "lots and lots of talking with lots and lots of people."

After two years of planning, the project was launched and continues to be successful because of four factors, Hammond said: clear scientific objectives, local support in the community where the research takes place, and good communication and trust among the scientists.

In Cuba, scientific collaboration with the United States is not a new phenomenon, said Pastrana. Cuban naturalist Felipe Poey was sharing his findings with the Smithsonian Institution as early as the 1850s, and a partnership between the Smithsonian and the Cuban Academy of Sciences continues today.

Continuity was also important when, after multiple visits to Cuba by AAAS leaders, the Academy of Sciences of Cuba and AAAS signed an agreement to foster joint cooperation in biomedical research, Pastrana said. These and other collaborations have been successful because they "have had the participation of scientists from Cuba and the United States all along. In the middle of all the difficulties that you know these two countries have had in the past, all the time we've been able to get across and talk about science," he said.

Scientists working under politically strained conditions aren't always representing different countries. "Tensive science" can also involve scientists who must collaborate along with political leaders during national or local emergencies, said Gary Machlis, who is the science advisor to the director of the National Park Service. He is also the co-leader of the Department of the Interior's Strategic Sciences Group (SSG), which conducts science-based assessments during crises such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and Hurricane Sandy.

This sort of work requires several distinct skills, including the ability to communicate the uncertainties of science to policy makers, which Machlis called "both essential and part an art form." The SSG typically uses a scale, ranging from "certain to not possible," that is attached to each of the potential policy implications associated with the group's scientific conclusions.

Machlis put forth five proposals for improving tensive science: researching best practices, investing in pre-crisis protocols, nurturing "back channels," training skilled science diplomats, and creating an international, neutral site where scientists can collaborate.

Summing up the session, organizer Frances Colón, acting deputy science and technology adviser to the U.S. secretary of state, highlighted the power of relationships as a theme common to the three presentations. "The science has to be solid, but the relationships must be in place," she said. Furthermore, these relationships "should not just be nurtured at the time of a crisis but…we have to have the foresight of maintaining and nurturing them" over the long term.

Kathy Wren, AAAS

[Edward W. Lempinen from TWAS contributed to this report]