[On 27 January 2017, President Donald Trump issued an executive order that imposed a 90-day travel ban, with some exceptions, on people from seven Muslim-majority countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. The order also suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program for 120 days. The order is currently being contested in the U.S. federal court system.

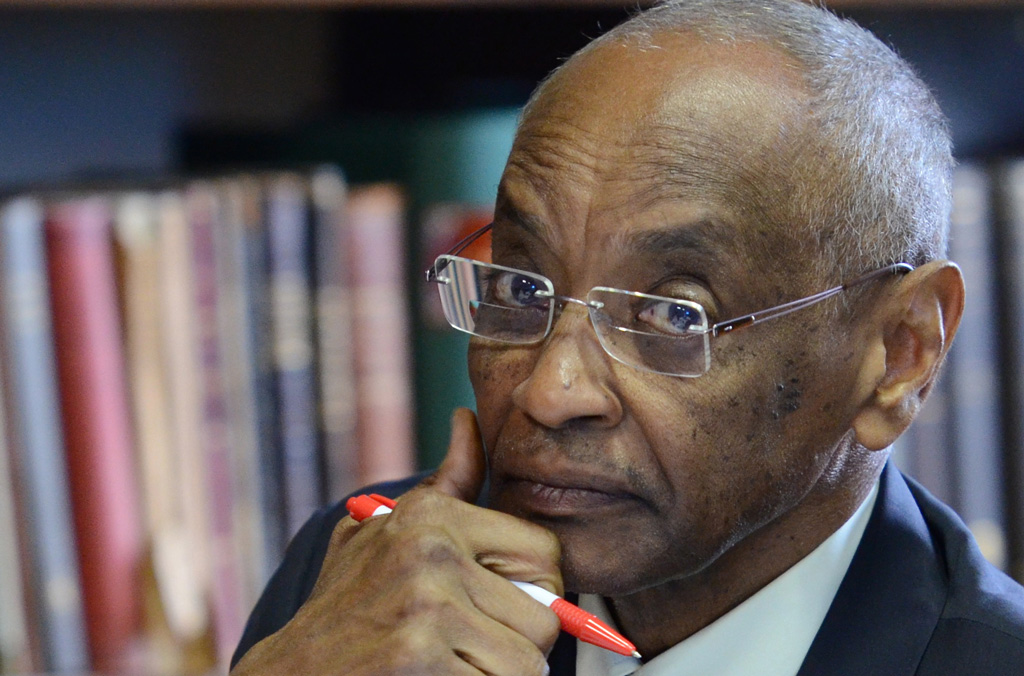

[The following is a statement in response to the U.S. travel ban by TWAS interim Executive Director by Mohamed Hassan. Professor Hassan is a Sudanese mathematican who also serves as president of the InterAcademy Partnership (IAP) and president of the Sudanese National Academy of Sciences. He has held a range of high-level science and education positions in a career spanning over 30 years.]

UPDATE: An abridged version of this statement has been published in the 16 February 2017 issue of the journal Science.

The United States is recognized internationally as a powerful leader in the realm of science and technology, with a system of innovation unmatched by any nation on Earth. It's understandable that researchers in the developing world often have great admiration for the United States – and this is true whether we're talking about the Arab region, Asia, Africa or Latin America. There are highly productive research networks that link these scientists with colleagues in the U.S. There is extensive research cooperation across all scientific fields – advanced biomedical technology, petroleum engineering and solar power, arid-land farming, disaster preparedness. In this day and age, science is truly international.

The United States is recognized internationally as a powerful leader in the realm of science and technology, with a system of innovation unmatched by any nation on Earth. It's understandable that researchers in the developing world often have great admiration for the United States – and this is true whether we're talking about the Arab region, Asia, Africa or Latin America. There are highly productive research networks that link these scientists with colleagues in the U.S. There is extensive research cooperation across all scientific fields – advanced biomedical technology, petroleum engineering and solar power, arid-land farming, disaster preparedness. In this day and age, science is truly international.

In this context, the executive order signed by the U.S. President on 27 January is profoundly disruptive. It will immediately have a negative effect on scientific research and the essential scientific processes of exchanging information and ideas. In the long run, the order will erode trust in the United States and undermine the sense that the US is a reliable partner for scientific research. This is very disturbing both for scientists from the developing world and for our colleagues in North America and Europe.

My own case provides an immediate example. I am a citizen of Sudan, and I have joint citizenship in Italy. I have lived and worked in Italy for more than 30 years, and I work with scientists and policymakers at very high levels in the United States and worldwide. There is constant travel, a constant exchange between international scientists. We meet, we hear presentations, we debate, and from this process flow ideas about new research, or new policy to support research.

Now, following this order, I have cancelled my arrangements to attend the annual meeting next week of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Why? Because I am Sudanese, and I am barred from traveling to the United States. The AAAS meeting is major event in the scientific calendar, and AAAS is a very close partner to TWAS. For example, we run a joint training programme in science diplomacy.

This year, I was supposed to attend the AAAS Annual Meeting and speak at a special ceremony to honour five young women scientists from the developing world who are winning prizes for their excellent research. The prize is offered by the Elsevier Foundation and the Organization for Women in Science in the Developing World – two large, mainstream science entities.

In fact, one of the prizewinners is from Sudan. Dr. Rania Abdelhameed Mokhtar is supposed to accept her award at the AAAS meeting, and this was to be an opportunity for her to meet many high-level international scientists. She received her visa a month ago for a routine, temporary visit – she was fully screened under the U.S. system. And now it apears that Rania may not be able to attend.

Without doubt, she has excellent credentials. She is director of the External Relation Office at the Sudan University of Science and Technology (SUST) in Khartoum. In 2011 she was appointed Director of Electronic Systems Research Centre at SUST. Her research is focused on high-impact national projects in the field of wireless communications engineering, agriculture automation sensors networks and security systems. She belongs to a number of front-line international scientific and engineering organisations.

Traveling to the U.S. was a great opportunity for her, but it was also a great opportunity for scientists at an international meeting to learn about her and her work. All of us can learn from each other – that is the nature of science. But now, that opportunity will likely be lost.

This is unfortunate for her and for others at the meeting. But consider the broader impact. After the award is announced, Rania will be greatly respected throughout Sudan. Among many young students, she will be seen as a hero. At the same time, they will hear that she has been blocked from attending the prize ceremony in the United States. They will ask: Why? And the answer is: Because she is from Sudan. Because she is a Muslim. And what will they think? People will say: See how they disrespect our scientists. See how they treat Muslims.

The premise of the U.S. executive order is that it is needed to keep the U.S. safe. But nobody from Sudan has ever committed a terrorist action against the United States. Some people have suggested that the order gives the terrorists leverage for recruiting new members, and I worry they could be right. It is unfortunate that the executive order seems to ignore this obvious cause-and-effect.

To minimize the risk of terrorism, it is vitally important to build partnerships, to build friendships – to build trust and goodwill. International scientific cooperation is a natural way to achieve that important goal.